via

http://ift.tt/2eCtIuu:

paxvictoriana:

@planb-becomeapirate asked: I have a question! lesbianism was taboo in victorian times and I’m assuming so was cross dressing? What is the explanation of pictures that exist where a woman is dressed up as a man and posing with another woman (who is a woman and it is strongly indicated they are a couple). For that matter, what is the explanation of photographs of women canoodling women? Did these ladies just not give a damn what people said?

First of all, THANK YOU: this is a great question.

I’m taking the bulk of my answer from Sharon Marcus’s *stellar* critical text, Between Women (2007), and TBH, if you wanted to read a full-length answer to your question – complete with citations, specifics, use of previous historians’ work, and further reading – you honestly could not do better than to go read BW right now.

**Here, though, I’m cutting to the highlights of Marcus’s book. Admittedly, it’s still a long post.**

1: Those photographs – including the one below – show, in many cases, pairs of women dressed, respectively, as male and female halves of a heterosexual couple. As Marcus stresses, way more Victorian and Edwardian women entered into what many knew as “female marriages” (aka same-sex couples, unrecognized of course by the law, but often perfectly acceptable to close friends and family) than one might assume. Female marriages – and this is how weird the Victorians could be at combining progressive and retrogressive thinking! – basically were seen to pose no threat to the gender system, since the end-goal of that system was to reinforce in every possible way the monogamous, procreative, married couple form.

Basically, women (and men, for that matter) who weren’t out cruising or having casual and multiple partners, who didn’t get too kinky or proclaim their unrestricted lifestyle, stayed on the “good” side of what Gayle Rubin identifies as the domino spectrum of “sexual peril” (“Thinking Sex”); crossing into random hook-ups in clubs, paying sex workers, or even becoming a sex worker yourself, all started down the road toward social irredeemability. Photographs were often taken for personal use and, since the apparatuses of photography were ever more available for individuals nearing and after the turn of the century, it was anything but impossible to get or even make portrait-quality photographs of female couples. (And of course, certain studios were prepared to take any nature of photograph – for a price.)

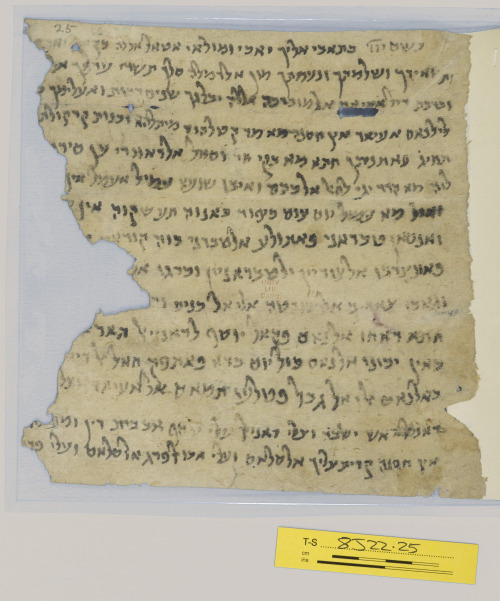

[Example photograph from 1910, apparently showing two women in, respectively, male and female dress. © Powerhouse Museum, Australia:]

Even famous women like Frances Power Cobbe – who, if you’ve never heard of her, you should look up IMMEDIATELY – were in such long marriages. Cobbe referred to her partner Marie Lloyd as (at one time or another) her “life-friend”, a ‘“truant husband” when Lloyd was traveling’, “my old woman”, and simply “my wife” (Marcus 52). Numerous other Victorians and Edwardians in same-sex relationships used similarly fluid and overlapping terms to refer to their partners and to themselves. It wasn’t as simple, then, as one partner being the ‘husband’ and the other the ‘wife’: the models for such things were available in the public consciousness, but in real people’s lives the terms were more useful in signaling the seriousness of the relationship for those in it, and to those who knew about it, than in setting their roles in stone.

2: HUGE for Marcus is pushing present-day readers to acknowledge that the category of “friends” – not just special friends *cough cough* but non-sexual and non-erotic, same-sex friends – was SO much more elastic than we tend to believe today. Codes of femininity stressed the essential difference between women and men, and thus stipulated (in all the ways social pressure can: parental advice, peer pressure from social circles, literary, visual, and commodity culture, etc.) that women be demure, innocent, passive, moral, and domestic in their dealings with men (who were, by contrast, encouraged to be bold, educated, enterprising, protective, and worldly… but not too worldly).

Relationships between women (as it were) gave the participants FAR more space to explore sides of themselves they were actively told to stifle in their lives beyond those friendship: women were assertive with their female friends, possessive, flirty, demanding, commanding (even domineering), callous, and loving, sometimes all with one friend over the course of one brief but volatile relationship, as well as in life-long beloved ones. Pairs and groups dressed up, went out together, met in clubs, vied for social favors, hugged, kissed, petted, admired, flattered, dressed, longed for, wrote long and passionate letters to, and relied on each other for support at the best and worst of times. Often, when a dear female friend visited her married one, the husband would relocate to a separate bedroom, leaving the women to sleep together and catch up. Whether many, or any, of these women engaged in sexual acts together is – Marcus emphasizes – not only unknowable, but missing the point. The intimacy of such friendships was seen to foster “feminine” feeling and (mad though this might seem to us in some instances) even help the married woman appreciate her husband and her role as wife, daughter, mother, sister, and ruler of the household.

3: Class. Class matters all the time, but for the Victorians class was ENORMOUSLY important, and was intertwined with gender and sexuality in ways both explicit and implicit. Marcus admits that most of the women, real and fictional, she covers in her book are middle-class, because that’s where so much Victorian/Edwardian energy went into establishing a pervasive code: women who desired upward social mobility had to enter and excel within the system, even as much as they were able to find elastic and plastic “play” within that system. Working-class women, however, didn’t have this luxury. In many cases, this was literally true: the luxury of free time, of spare objects to trade as gifts on beloved friends, of room to invite other women to stay, of the dress/costumes for showing off or cross-dressing (whether for fun or as a self-fashioning of their preferred gender identity) – all these and more were simply not available to women who often had to pawn their few possessions on a weekly basis just to keep food on the table. These women – as scholars like Judy Walkowitz, Olwen Hufton, and Ellen Ross all explain – did heavily rely on tight bonds of female sociability, whether this was in sharing what little they did have (washing tubs, pins and needles to repair clothes since new ones were beyond the budget, food, knowledge); pooling their labor so that they could collectively keep their eyes on more children than any one woman could mind alone; even passing on critical knowledge about sex, childbirth and child-rearing, abortions, money and household economy, and political agitation and action that would affect them as much as their husbands, fathers, brothers, and other male relations.

Lots of the examples in lesbian and other queer history (within the British context anyway) refer to upper-class women, because their blatant disregard for normative behavior was, obviously, tolerated because, yes, they didn’t have to care. Anne Lister, as early as the 1820s, used her large estate in Yorkshire as a home for herself and her two successive partners: first, Mariana Lawton, and later, Ann Walker (to whom she considered herself married from 1834 until her death). Lister often chose stereotypically “male” dress and referred to herself by a male pronoun and the name “gentleman Jack”. (So, for that matter, did author and artist Violet Paget at the the other end of the century, preferring her/his penname “Vernon Lee”.) But even that kind of story doesn’t end well once the legally-indisputable owner of the estate is gone: after Lister died, and despite that they shared their respective properties and that in her will Lister had left Walker a lifetime lease on Shibden Hall (where they’d lived together as married), Lister’s distant family took “less than two years to declare Ann [Walker] mentally unstable and incompetent to manage the two estates”, had her committed to an asylum, and left her there until her death in 1854. Even when big money had protected them, these and many more 19th-century women discovered how precarious their circumstances were, and how their gender and romantic/erotic lives could have major consequences for their financial ones.

[Image: Fanny and Stella, born Frederick Park and Ernest Boulton, and discussed by Neil Bartlett for how they transgressed Victorian codes and forced a “contortion of the law” in order for their lifestyles to pass, as it were, under the radar. Photographed together – according to the Essex Record Office – ca. 1869:]

4: Coda. It’s worth keeping in mind that, for the Victorians, one of the central tenets of succeeding in society – not just getting into the good parties, but in having anyone look at you in the street, having friends who would visit you, having vendors who would take your business, keeping either your servants or, if you were a worker yourself, your job – came down to what might be termed plausible deniability: or, perhaps another way of putting it, public, tacit knowledge. As long as you didn’t make a scene, didn’t rock the boat, didn’t flaunt your difference, things could and definitely go on in private pretty much as you chose. Even working-class women definitely dressed as men in order to get work that was, increasingly over the century, exclusive to male laborers, but the rule came down to, to borrow a proleptic phrase, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”. But once you, like Oscar Wilde or Fanny and Stella (pictured above), crossed that line and started to rub people’s noses in it – started to enjoy the hypocrisy of an “open secret” a little too much, and made the powers that be feel like they were being mocked to their faces – in short, once you forced that private, tacit knowledge to become explicit, your life could go very wrong, very quickly.

* * *

There’s so much more to say, so I hope anyone interested checks out Marcus (Between Women), Walkowitz (Prostitution and Victorian Society), Olwen Hufton (on the economy of “makeshift”), Ellen Ross (Love & Toil), Gayle Rubin (“Thinking Sex”), Martha Vicinus (Intimate Friends), Judith Butler (Gender Trouble, especially the final chapter on drag), Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (Between Men and always The Epistemology of the Closet), and all the various historians and theorists those works refer to and rely on.

THANKS FOR THE ASK, @planb-becomeapirate! I welcome any and all questions on matters Victorian: submit your question here.

*UPDATE*: here’s my first follow-up post, addressing a few more questions about Victorian words and notions around female homosexuality.